In 1960, there were about 11,000 houses and apartments in Windham county, which includes Brattleboro. By 2000, that number had more than doubled to reach 27,000. Similar growth has happened throughout the Valley.

In itself, that change isn't bad: people need homes and builders need jobs. The problem is that very few of those new homes were built in areas like Main Street, Brattleboro. Most homes in the last several decades have been constructed in remote forests or on prime farmland. Almost all require their occupants to have a car, unlike houses in downtown Brattleboro, which are close to shopping, jobs, and the bus and train stations.

A Trust for Public Land report, "The Connecticut River: Quintessential New England," tells a shocking story with numbers: the number of people living in the entire length of the Connecticut River valley grew just eight percent from 1980 to 2000. But the amount of developed land grew 33 percent from 1982 to 1997.

That's partly because people are building more vacation homes and partly because the houses people live in year-round are getting bigger. They're also being built in more remote locations, requiring more road construction. Between 1982 and 2000, the report shows, the Connecticut River Valley lost 27 percent of its farmland. It's almost too painful to try to imagine what Windham County would look like if all the land that is vulnerable to being paved for roads, Chem-Lawned, or covered with concrete foundations — the vast majority of the county — was developed. Picture suburban Los Angeles, eastern Massachusetts or Long Island.

Of course, the slow swallowing up of large swaths of land isn't going unnoticed in Vermont. One solution residents have proposed to stave off the spread of rural sprawl in the state is the creation of community forests. This kind of proposal, which supporters say can also maintain jobs for loggers and maple syrup farmers, is close to fruition an hour's drive up the road from Windham County.

At town meeting in 2006, residents of West Fairlee voted unanimously to support the project and by February, the towns of Fairlee, Bradford, and West Fairlee expect to know if they will have secured the funding needed to create a 3,400 acre forest that will be protected from development in perpetuity.

"It is very likely that this project will go through," Rodger Krussman told the Valley Post. He works for the Montpelier office of Trust for Public Land, a national non-profit organization based in San Francisco.

Right here in Windham County, several efforts to curb rural sprawl have been launched, but they have received varying levels of support. In some towns, zoning has been revised to encourage more "smart-growth" development, or funds have been set up so communities can purchase open land and preserve it. But so far, there is no single concentrated initiative working to stem the flow of development. There are, however, a set of officials, residents and activists who are starting to view rural sprawl as a major piece of big-picture environmental concerns.

Brattleboro Selectboard member Richard Garant said the town's new Peak Oil Committee has concluded that to deal with problems like global warming and predicted increases in oil prices, officials need to examine more than basic energy use habits.

"Changing to efficient light bulbs is nice, but it isn't enough," Garant said. "We've got to look at land use and transportation. How can you have effective bus service when new houses are being built half a mile from the nearest existing house?"

Close to home

Not all land that's protected from development is kept as wilderness. Farmers and major forestland owners in Windham County have increasingly been selling development rights to conservation groups. The land-owners retain the right to continue farming or logging their land using sustainable methods; in some cases they even retain the right to post "No Trespassing" signs. But the land can never be used for buildings or paved roads.

Another method of slowing rural sprawl is to renovate and redevelop existing structures. In downtowns like Wilmington and Bellows Falls, for example, run-down single-family homes can be replaced with small, energy-efficient apartment buildings.

That's one strategy that Brattleboro is pursuing. According to Town Manager Barbara Sondag, the town is funding an initiative to help people create affordable apartments in vacant rooms or as additions to their property. The program promotes additional housing units and an efficient use of already-developed land.

By contrast, Dummerston has a farmland protection fund. This fund can be used for protecting farm and forest-land, as long as the forest land is being used for some kind of agricultural purpose (like maple syrup production and possibly logging). Unfortunately, the fund has never had enough money in it to buy any land. The fund is now worth about $13,000.

Many other towns have put money in open space protection programs, and officials have used the funds to buy land and protect it from development. Charlotte, a town of 2,000 in Chittenden County, has designated $100,000 for its open space fund in recent years.

A town just over the river from Windham County, Chesterfield, N.H., is home to about 3,800 people. In 2006, Chesterfield used $51,000 from its open space protection fund to buy land. The town still has about $150,000 in the fund.

North, in Rockingham, Zoning Administrator Ellen Howard said the town has tried to control sprawl by setting up 25-acre and five-acre zoning districts.

"Rockingham's sprawl has been restricted by the type of topography we have here, and the soil types for waste water systems," she added.

Selectboard member Thomas MacPhee said the state's so-called "current use" property tax program was protecting open space in Rockingham, though he noted that property owners can build on land in that program by paying a fee to the state.

Zoning is one way of addressing scattered development of open land, according Don Webster of Brattleboro, a former state legislator who is also a member of the board of directors of Smart Growth Vermont, a non-profit in Burlington. But, he said, it "doesn't necessarily stop sprawl," he said.

"[Zoning] can have unintended consequences. The best way to stop sprawl is to encourage affordable housing in existing downtowns, and to support the work of groups like the Vermont Land Trust."

The Vermont Land Trust is the only organization devoted to protecting farm- and forest-land with staff based in Windham County. The non-profit, which says it has protected almost half a million acres in the state since it was founded in 1977, has an office on Linden Street in Brattleboro.

The work of the Land Trust and various other initiatives to preserve open space and limit development might also a break when it comes to municipal taxes.

According to a study by the Vermont League of Cities and Towns, preserving open space can be a boon to taxpayers. A league report showed that towns with the most protected open space have the lowest property taxes. In sum, towns that have to provide fewer updates to infrastructure or have, conversely, more geographically concentrated public works and services, also tend to offer lower municipal tax rates. The findings can be found at www.vlct.org under The Land Use — Property Tax Connection.

John Pucher is professor of land use at Rutgers University. His widely published research compares land use in Europe and the United States. Pucher says rural towns in Europe keep homes and businesses within easy walking distance of one another. Most people in rural Europe don't own cars because they don't need them; they can easily walk or ride a bicycle to shop, to get to school or work, or to the train station if they need to go to the city or another town. It's also easy to walk from the center of a town of 5,000 or 10,000 people to the edge of town, from which miles of uninterrupted farm and forest land extend in all directions.

When rural Americans go somewhere, 98 percent of the time they go by private automobile, Pucher said. That's a problem for people in rural areas who are too young or too old to drive. Pucher added that dependence on cars is bad for the environment, and even for health, because it causes obesity.

Support for regionally planned growth in New England, akin to the variety seen in Europe, does exist. Brad Campbell is spokesman for the Western Massachusetts chapter of the National Association of Homebuilders. Campbell says his group is not opposed to preserving open space — if zoning laws are changed so more homes can be built closer together in designated areas.

If open space protection results in a net loss of jobs in the construction industry — a question that's open for debate — it certainly results in an increase in jobs in agriculture, logging and tourism. The recent growth in demand for locally-grown, organic food could mean farmers in Windham county will be able to hold onto their land or even expand, hire more workers, and pay better wages.

A problem with the way development has proceeded in Windham County so far is that it's often the result of a conversation between a corporation or contractor and an overwhelmed, all-volunteer local planning board, and involves little input from the public. Ordinary people who live outside the town where the development is planned almost never have a say, even though they may be affected.

Most land use planning in rural areas of the United States is done by town commissions run by volunteers with little or no formal training. When these volunteer commissions try to preserve open space, they often go up against wealthy developers with teams of well-paid lawyers. They're also battling many landowners' views that zoning regulations are unnecessary and that no one should tell private land owners what they can and can't do with their land.

But there are victories for volunteer efforts, too. Grassroots preservation projects have also had notable successes protecting farm- and forest-land in Windham County.

The Putney Mountain Association, which has a web site, and the Windmill Hill Pinnacle Association, both all-volunteer run, together have protected hundreds of acres in eastern Windham County in recent years.

In the northwestern corner of the county, the all-volunteer Stratton Area Citizens Committee has been active since 1984, mainly fighting plans by Intrawest Corporation to build vacation homes in remote forests. Intrawest has 24,000 employees and $1.3 billion in annual sales. "We stopped them from putting in 500 condos and a golf course," said Committee member Darlene Palola. "Now we're fighting a developer who wants to put 16 houses in the pristine Kidder Brook watershed. We can use all the volunteers and donations we can get."

-----------

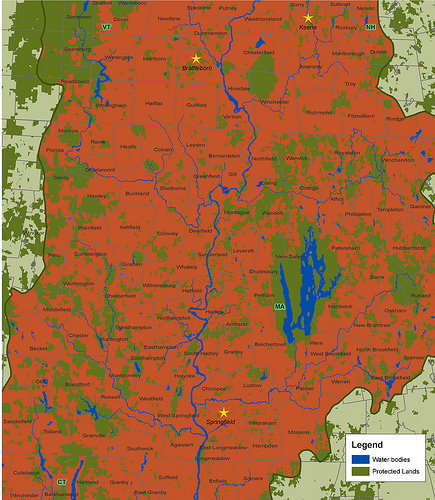

Map by the Trust for Public Land, 2006. This map shows the Pioneer Valley section of the Connecticut River watershed. Land outside the watershed is light green, meaning streams in that area do not flow to the Connecticut River. Dark green land has been protected from development. Red land is vulnerable to being paved with McMansions, Wal-Marts, parking lots, roads, and ChemLawns. Click on the map to enlarge.

Post new comment