This month, the state of Vermont gave the all-volunteer run Windmill Hill Pinnacle Association $591,000 to buy land near Brattleboro. The Pinnacle is the highest and most scenic peak in Westminster, Vermont, near Brattleboro. From the Pinnacle you can see Stratton Mountain, more than 20 miles away. The Windmill Hill Pinnacle Association owns 1,662 acres in Rockingham, Athens, Brookline, and Westminster, all of which is open to the public. There is a 14 mile hiking trail and a wildlife sanctuary. Details are at www.windmillhillpinnacle.org

Other groups in the Valley that are saving farm and forest land from development include:

www.monadnockconservancy.org in Keene;

www.franklinlandtrust.org in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts, near Greenfield;

www.vlt.org a statewide group with an office in Brattleboro;

www.kestreltrust.org in Amherst;

www.thetrustees.org a statewide group based near Boston with staff based in the Valley.

--------

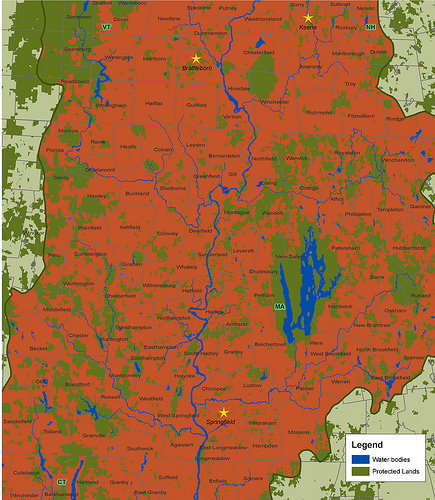

Map by the Trust for Public Land, 2006. This map shows the Pioneer Valley section of the Connecticut River watershed. Land outside the watershed is light green, meaning streams in that area do not flow to the Connecticut River. Dark green land has been protected from development. Red land is vulnerable to being paved with McMansions, Wal-Marts, parking lots, roads, and ChemLawns. Click on the map to enlarge.

------------------

My father worked on the last dairy farm on Long Island. Now the farm is long gone and my father farms in the Hudson River Valley. I was too young when that farm closed to remember whether any newspaper published an article to mark the occasion. But it seems unlikely that any did.

When will the loss of farmland and forest here in the Pioneer Valley become a major news story? Will that happen while there are still any working farms and big stands of forest left to save?

Clem Clay works in a nondescript office in Northampton for the Trust for Public Land, a national group that says it has protected some 2 million acres of land from development since it opened its doors in 1972.

That's an impressive number, but here in the Valley, it seems fair to say that land preservationists are losing the race to “build-out.” That’s the finish line in the land use planning process, where every piece of land is either built on, or protected.

For the past decade, Massachusetts lost some 40 acres of open space to development every day. In the decade of the 1990s, approximately 81,000 single-family houses were built in the four counties of Western Massachusetts.

In Hampshire and Hampden counties alone, more than 1,500 acres of open space have been lost every year for the past 20 years. That loss is, for practical purposes, irreversible; the chances of a Wal-Mart or a McMansion being torn down and replaced with prime farmland or wilderness are slim to none.

Clay and other conservationists are quick to say they’re not opposed to construction of new homes and businesses. They just want it to happen in existing downtowns, like Springfield, Greenfield, and Brattleboro. Run-down single-family homes can be replaced with small, energy-efficient apartment buildings. New stores can be built on the vast, usually half-empty parking lots around strip mall shopping centers. If more parking is really needed, multi-story garages can be erected.

Support for this kind of regionally planned growth comes from some unexpected quarters. Brad Campbell is spokesman for the Western Massachusetts chapter of the National Association of Homebuilders. Campbell says his group is not opposed to preserving open space—if zoning laws are changed so more homes can be built closer together in designated areas.

Protecting open land and building new homes and commercial buildings in existing downtowns (by buying and demolishing rundown or vacant buildings) means changes for the construction industry, one of the biggest employers in the Valley. Construction workers need to be retrained, and enforcement of safety rules is paramount. Demolition and renovation involve health hazards that new construction doesn’t.

If open space protection does result in a net loss of jobs in the construction industry—a question that’s open for debate—it certainly results in an increase in jobs in agriculture, logging and tourism. The recent growth in demand for locally grown, organic food has meant farmers in the Valley can hold onto their land or even expand, hire more workers, and pay better wages. In Vermont, for example, demand for organic milk is reviving the dairy industry and, in a surprising reversal of a long trend, even attracting people to leave other occupations and go into dairy farming.

Clay’s report, “The Connecticut River: Quintessential New England,” tells a shocking story with numbers: the number of people living in the entire length of the Valley grew just eight percent from 1980 to 2000. But the amount of developed land grew 33 percent from 1982 to 1997.

That’s partly because people are building more vacation homes that are usually empty, and partly because the houses people live in year-round are getting bigger. They’re also being built in more remote locations, requiring more road construction.

Between 1982 and 2000, the report shows, the Connecticut River valley lost 27 percent of its farmland. The report is illustrated with half a dozen colorful maps of the region, one of which is reprinted with this article. It shows land that has been protected from development in dark green; unprotected land is red. (The light green area is unprotected land that’s outside the Valley, or “watershed.”)

It’s almost too painful to try to imagine what the Pioneer Valley would look like if all the land that is vulnerable to being paved for roads, Chem-Lawned, or covered with concrete foundations—the vast majority of the Valley—was developed. Picture suburban Los Angeles, eastern Massachusetts or Long Island.

“We’re constantly racing to beat development,” says Mary Shanley-Koeber. She’s lived in Whately and worked for Mass Audubon, a state-wide environmental group, for the past 19 years. “Our work is big, but I have a lot of hope about what can be done.”

In March, Shanley-Koeber’s group announced it had raised enough money to buy 26 acres in Williamsburg that had, she said, been slated for construction of “trophy homes.” The land is now a wildlife refuge.

Easthampton mayor Mike Tautznik has fought successfully to protect hundreds of acres of open space in his town in recent years. Tautznik says he couldn’t have done it without the support of the majority of residents.

In Westfield, the Winding River Land Conservancy was formed in 1999. In its first few years in business, the group had already helped preserve more than 700 acres of land.

Not all land that’s protected from development is kept as wilderness. Farmers and major forest land owners in the Valley have increasingly been selling development rights to conservation groups. The land owners retain the right to continue farming or logging their land using sustainable methods; in some cases they even retain the right to post No Trespassing signs. But the land can never be used for buildings or paved roads.

For every land conservation victory Shanley-Koeber has racked up in her nearly two decades of doing battle, there have been losses: the recent loss of farmland at the base of Mount Tom on East Street in Easthampton, for example.

And the threats keep mounting. Shanley-Koeber describes forest land in hill towns like Whately, Williamsburg and Conway as among the most endangered open spaces in the Valley.

Clay notes that the New England Council, an industry association, has identified the Valley as a “top site for new business development.” National Realty and Development of Purchase, N.Y. is heeding the call: the company wants to build a retail complex half the size of the mammoth Holyoke Mall at Ingleside directly over the recharge area for the Barnes Aquifer in Westfield.

Paving and building, even apart from the human activities associated with development, are threats to ground- and surface water, partly because surfaces like roads become polluted with oil and salt, and partly because pavement interferes with the intricate filtration that occurs when water can soak into the ground before migrating to aquifers, ponds and rivers. The federal Environmental Protection Agency says water in the Connecticut River will become polluted when the percentage of the Valley’s land covered with “impervious” surfaces (roofs, roads) hits 10 percent.

And flooding is a very real danger up and down the Connecticut River valley. In 2005, a heavy rain washed away a trailer park in Greenfield, leaving its residents homeless, and did several million dollars’ worth of damage in Springfield. Many low-lying areas flood from time to time, and residents suffer minor, or major, property damage. Open land mitigates flooding by soaking in excess water.

After the legendary flood of 1936 in the Valley, the federal government erected a series of 16 flood control dams on the Connecticut River. Clay notes that these will eventually need to be replaced—a costly proposition. Buying open space could be a better deal. “By protecting land in strategic areas that are capable of absorbing large amounts of floodwater by virtue of their expanses of flat land near the river,” he writes, “it is possible to provide important flood management capacity while also protecting farmland, [wildlife] habitat, and the river’s need to wander through its floodplain over time."

A problem with the way development has proceeded in the Valley so far is that it’s often the result of a conversation between a corporation or contractor and an overwhelmed, all-volunteer local planning board, and involves little input from the public. Ordinary people who live outside the town where the development is planned almost never have a say, even though they may be affected—when development is proposed for an aquifer recharge area that serves several towns, like the Barnes Aquifer, for example.

What can ordinary, busy people who want to help protect open land in the Valley do? If you hear from a neighbor that a piece of open land is at risk for development, contact a land conservation group, says Jocelyn Forbush. She works in Holyoke for the Trustees of Reservations, one such group.

Even better, get involved in your town’s land use planning process before “for sale” signs start going up in front of your favorite scenic farm field or remote forest waterfall. Speak out at planning commission and selectboard meetings.

Help bust the myth that more development will reduce property taxes. A recent study by the Vermont League of Cities and Towns is among several studies that have found that the New England towns that have preserved the most land from development have the lowest property taxes. That’s because they don’t need to spend as much on services like police and fire protection, roads and schools.

Many small towns in the Valley have no public sewer or water systems. This means new houses must be built far apart from one another to prevent neighbors’ sewage and drinking water mixing. So installing public water and sewer systems is an effective way to protect open space by allowing new development to happen in town centers. Putney, Vt. installed such a system last year.

To try to control sprawl, in 2000 Massachusetts passed the Community Preservation Act. The Act lets towns receive matching funds from the state for open space preservation, affordable housing, and historic preservation. Federal funds are often available to match local and state money spent on land preservation.

Stockbridge joined the state fund in 2003. In 2005, Stockbridge taxed itself $200,000 and got an equal amount from the state. The town now has a bank account with money to buy open land that becomes threatened by development. But most towns in the Valley have yet to tap into the Act.

People who want to keep the Valley from looking like Long Island can also call their state legislators and ask them to back pending zoning reform legislation, says Nancy Goodman, a lobbyist at the Environmental League of Massachusetts.

“Under the current rules, if you have enough road frontage, you can build anywhere in the state without having to apply for a local permit,” Goodman said. “We want to change that.”

Connecticut is the only state in the nation that’s losing farmland to development faster than Massachusetts, according to American Farmland Trust.

Another weapon in the arsenal of activists determined to protect open space is civil disobedience. Across the country, it’s had some memorable successes. In the summer and fall of 1997, more than 1,000 people were arrested for protesting plans by Maxxam Corp. to log an ancient redwood forest near Eureka, Calif. Within months of the protests, the federal government bought 7,500 acres to create the Headwaters Forest Preserve.

Land Use Done Right

Most land use planning in rural areas of the United States—including those in the Valley—is done by town commissions run by volunteers with little or no formal training. When these volunteer commissions try to preserve open space, they often go up against wealthy developers with teams of well-paid lawyers. They’re also battling many landowners’ views that zoning regulations are unnecessary and that no one should tell private land owners what they can and can’t do with their land.

In Europe, by contrast, most land use planning is done at the state and national level. European planners are usually trained, full-time professionals.

John Pucher is professor of land use at Rutgers University. His widely published research compares land use in Europe and the United States. Pucher says rural towns in Europe keep homes and businesses within easy walking distance of one another. Most people in rural Europe don’t own cars because they don’t need them; they can easily walk or ride a bicycle to shop, to get to school or work, or to the train station if they need to go to the city or another town. It’s also easy to walk from the center of a town of 5,000 or 10,000 people to the edge of town, from which miles of uninterrupted farm and forest land extend in all directions.

By comparison, most people who live in rural areas of the U.S—like the Valley—are dependent on their cars because homes are often miles from shopping, schools and work places. The tradeoff is that most homes in rural Europe do not have back yards, or, if they do, they’re much smaller than yards in the rural U.S.

When rural Americans go somewhere, 98 percent of the time they go by private automobile, Pucher said. That’s a problem for people in rural areas who are too young or too old to drive. Pucher added that dependence on cars is bad for the environment, and even for health, because it causes obesity.

paintingLand protected through citizen action.

paintingLand protected through citizen action.

---------

A shorter version of this article was published in 2006.

Post new comment