Massachusetts loses some 40 acres of open space to development every day. Every year, about 8,000 single-family houses are built in the four counties of western Massachusetts. In Hampshire and Hampden counties alone, more than 1,500 acres of open space have been lost every year for the past 20 years. That loss is, for practical purposes, irreversible; the chances of a Wal-Mart or a McMansion being torn down and replaced with prime farmland or wilderness are slim to none.

On May 27, Republican governor Jim Douglas of Vermont vetoed legislation that environmental groups said is critical to saving the state's farm and forest land. If enough Vermonters call their legislators, the House and Senate can override Douglas. More information on that is at www.vlt.org/current-use.html

A spokeswoman for the New England office of the Trust for Public Land www.tpl.org told the Valley Post last week that the picture for open space protection funding in New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and nationally, is mixed.

"Obama made a big commitment to conservation funding," said Kim Gilman. "But Congress has been raiding that fund for other purposes [like war and road building]. In Massachusetts, Governor Patrick in 2007 signed a bond for open space protection for $50 million annually for five years. So far, the state has followed through with that funding, but we're concerned that they may cut the funding."

Also in 2007, the governor of New Hampshire signed legislation to raise and spend $6 million annually on protecting open space. "That funding has been cut," the Trust's Gilman said.

Land conservation activists say they aren't opposed to construction of new homes and businesses. They just want it to happen in existing downtowns, like Keene, Holyoke, and Brattleboro. Run-down single-family homes can be replaced with small, energy-efficient apartment buildings. New stores can be built on the vast, usually half-empty parking lots around strip mall shopping centers. If more parking is really needed, multi-story garages can be erected.

Support for this kind of regionally planned growth comes from some unexpected quarters. Brad Campbell is spokesman for the Western Massachusetts chapter of the National Association of Homebuilders. Campbell says his group is not opposed to preserving open space -- if zoning laws are changed so more homes can be built closer together in designated areas.

Protecting open land and building new homes and commercial buildings in existing downtowns (by buying and demolishing rundown or vacant buildings) means changes for the construction industry, one of the biggest employers in the Valley. Construction workers need to be retrained, and enforcement of safety rules is paramount. Demolition and renovation involve health hazards that new construction doesn't. Union workers usually get better pay, benefits, and training, and work under safer conditions.

------------

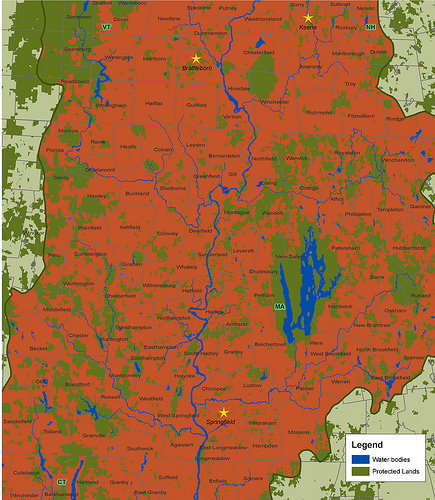

Map by the Trust for Public Land, 2006. This map shows the Pioneer Valley section of the Connecticut River watershed. Land outside the watershed is light green, meaning streams in that area do not flow to the Connecticut River. Dark green land has been protected from development. Red land is vulnerable to being paved with McMansions, Wal-Marts, parking lots, roads, and ChemLawns. Click on the map to enlarge.

------------------

Open space protection creates jobs in agriculture, logging and tourism. The recent growth in demand for locally grown, organic food has meant farmers in the Valley can hold onto their land or even expand, hire more workers, and pay better wages. In Vermont, for example, demand for organic milk is reviving the dairy industry and, in a surprising reversal of a long trend, even attracting people to leave other occupations and go into dairy farming.

The number of people living in the entire length of the Valley grew just eight percent from 1980 to 2000. But the amount of developed land grew 33 percent from 1982 to 1997.

That's partly because people are building more vacation homes that are usually empty, and partly because the houses people live in year-round are getting bigger. They're also being built in more remote locations, requiring more road construction.

Between 1982 and 2000, a TPL report shows, the Connecticut River valley lost 27 percent of its farmland. The report is illustrated with half a dozen colorful maps of the region, one of which is reprinted with this article.

It's almost too painful to try to imagine what the Pioneer Valley would look like if all the land that is vulnerable to being paved for roads, Chem-Lawned, or covered with concrete foundations -- the vast majority of the Valley -- was developed. Picture suburban Los Angeles, eastern Massachusetts or Long Island.

"We're constantly racing to beat development," said Mary Shanley-Koeber. She has lived in Whately and worked for Mass Audubon, a state-wide environmental group, for the past 19 years. "Our work is big, but I have a lot of hope about what can be done."

In Westfield, Massachusetts the Winding River Land Conservancy was formed in 1999. By 2005, the group had already helped preserve more than 700 acres of land.

Not all land that's protected from development is kept as wilderness. Farmers and major forest land owners in the Valley have increasingly been selling development rights to conservation groups. The land owners retain the right to continue farming or logging their land using sustainable methods; in some cases they even retain the right to post No Trespassing signs. But the land can never be used for buildings or paved roads.

------------

This photo, taken last summer, shows the Scott Farm in Dummerston, Vermont in the foreground, New Hampshire's Mount Wantastiquet in the distance, and Brattleboro in-between. The 600 acre Scott Farm -- where the movie "The Cider House Rules" was filmed -- is vulnerable to development. Mount Wantastiquet is a state park. There are many energy efficient apartment buildings -- and an Amtrak station -- in Brattleboro. (To make the photo bigger please click on it, then scroll down and click, "See full size image.") photo by Eesha Williams

-------------

Shanley-Koeber describes forest land in Massachusetts hill towns like Whately, Williamsburg and Conway -- near Greenfield -- as among the most endangered open spaces in the Valley.

Paving and building, even apart from the human activities associated with development, are threats to ground- and surface water, partly because surfaces like roads become polluted with oil and salt, and partly because pavement interferes with the intricate filtration that occurs when water can soak into the ground before migrating to aquifers, ponds and rivers. The federal Environmental Protection Agency says water in the Connecticut River will become polluted when the percentage of the Valley's land covered with impervious surfaces (roofs, roads) hits 10 percent.

And flooding is a very real danger up and down the Valley. Many low-lying areas flood from time to time, and residents suffer minor, or major, property damage. Open land mitigates flooding by soaking up excess water.

After the legendary flood of 1936 in the Valley, the federal government erected a series of 16 flood control dams on the Connecticut River. Clem Clay of the Trust for Public Land notes that these will eventually need to be replaced -- a costly proposition. Buying open space could be a better deal. "By protecting land in strategic areas that are capable of absorbing large amounts of floodwater by virtue of their expanses of flat land near the river," he wrote in a TPL report, "it is possible to provide important flood management capacity while also protecting farmland, [wildlife] habitat, and the river's need to wander through its floodplain over time."

A problem with the way development has proceeded in the Valley so far is that it's often the result of a conversation between a corporation or contractor and an overwhelmed, all-volunteer local planning board, and involves little input from the public. Ordinary people who live outside the town where the development is planned almost never have a say, even though they may be affected -- when development is proposed for an aquifer recharge area that serves several towns, like the Barnes Aquifer, for example.

What can ordinary, busy people who want to help protect open land in the Valley do? If you hear from a neighbor that a piece of open land is at risk for development, contact a land conservation group, says Jocelyn Forbush. She works in Holyoke for the Trustees of Reservations, one such group.

Even better, get involved in your town's land use planning process before "for sale" signs start going up in front of your favorite scenic farm field or remote forest waterfall. Speak out at planning commission and selectboard meetings.

Help bust the myth that more development will reduce property taxes. A recent study by the Vermont League of Cities and Towns is among several studies that have found that the New England towns that have preserved the most land from development have the lowest property taxes. That's because they don't need to spend as much on services like police and fire protection, roads and schools.

Many small towns in the Valley have no public sewer or water systems. This means new houses must be built far apart from one another to prevent neighbors' sewage and drinking water mixing. So installing public water and sewer systems is an effective way to protect open space by allowing new development to happen in town centers. Putney, Vermont installed such a system in 2005.

To try to control sprawl, in 2000 Massachusetts passed the Community Preservation Act. The Act lets towns receive matching funds from the state for open space preservation, affordable housing, and historic preservation. Federal funds are often available to match local and state money spent on land preservation.

Stockbridge joined the state fund in 2003. In 2005, Stockbridge taxed itself $200,000 and got an equal amount from the state. The town now has a bank account with money to buy open land that becomes threatened by development. But most towns in the Valley have yet to tap into the Act.

Connecticut is the only state in the nation that's losing farmland to development faster than Massachusetts, according to American Farmland Trust.

People can call their state and federal elected officials and ask them to boost funding for land conservation.

Finally, another weapon in the arsenal of activists determined to protect open space is non-violent civil disobedience. Across the country, it's had some memorable successes. In the summer and fall of 1997, more than 1,000 people were arrested for protesting plans by the Texas-based Maxxam Corporation to log an ancient redwood forest near Eureka, California. Within months of the protests, the federal government bought 7,500 acres to create the Headwaters Forest Preserve.

POSTSCRIPT: Land Use Done Right

Most land use planning in rural areas of the United States --including those in the Valley -- is done by town commissions run by volunteers with little or no formal training. When these volunteer commissions try to preserve open space, they often go up against wealthy developers with teams of well-paid lawyers. They're also battling many landowners' views that zoning regulations are unnecessary and that no one should tell private land owners what they can and can't do with their land.

In Europe, by contrast, most land use planning is done at the state and national level. European planners are usually trained, full-time professionals.

John Pucher is professor of land use at Rutgers University. His widely published research compares land use in Europe and the United States. Pucher told the Valley Post that rural towns in Europe keep homes and businesses within easy walking distance of one another. Most people in rural Europe don't own cars because they don't need them; they can easily walk or ride a bicycle to shop, to get to school or work, or to the train station if they need to go to the city or another town. It's also easy to walk from the center of a town of 5,000 or 10,000 people to the edge of town, from which miles of uninterrupted farm and forest land extend in all directions.

By comparison, most people who live in rural areas of the U.S. -- like the Valley -- are dependent on their cars because homes are often miles from shopping, schools and work places. The tradeoff is that most homes in rural Europe do not have back yards, or, if they do, they're much smaller than yards in the rural U.S.

When rural Americans go somewhere, 98 percent of the time they go by private automobile, Pucher said. That's a problem for people in rural areas who are too young or too old to drive. Pucher added that dependence on cars is bad for the environment, and even for health, because it causes obesity.

One group that's trying to get the government to transfer funds from road building to Amtrak is the National Association of Rail Passengers www.NARPrail.org

paintingLand protected through citizen action. painting by Eesha Williams

paintingLand protected through citizen action. painting by Eesha Williams

Pavers

A good planning tool is a small tax on real-estate transactions that goes to local land preservation. First-time home buyers are exempt. This quickly builds up a reserve that the the town or village can use to acquire open space that is especially environmentally sensitive, protect water, oe simply much-loved. Our town has had this for about 15 years--it was passed over strong objections from real estate agents--it has worked wonderfully. I wish we had had it for the past 50 years. (Now even the real estate agents are happy because open space has added so much value to the community).

Post new comment